What Is Psoriasis*

Psoriasis is a chronic, non-infectious, painful, disfiguring and disabling autoimmune disease for which there is no cure and with great negative impact on a persons’ quality of life. It can occur at any age, and is most common in the age group 50–69. Due to the number of people with psoriasis, it is a serious global problem.

The etiology of psoriasis remains unclear, although there is evidence for genetic predisposition. The role of the immune system in psoriasis causation is also a major topic of research. Psoriasis can also be provoked by external and internal triggers, including mild trauma, sunburn, infections, systemic drugs and stress.

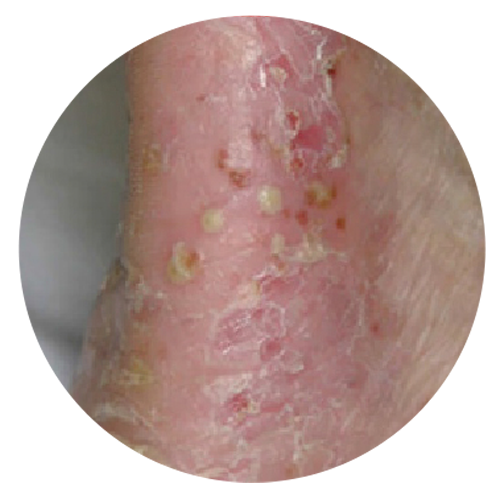

Psoriasis involves the skin and nails, and is associated with a number of co-morbidities. Skin lesions are localized or generalized, mostly symmetrical, sharply demarcated, red papules and plaques, and usually covered with white or silver scales. Lesions cause itching, stinging and pain. Between 1.3% and 34.7% of individuals with psoriasis develop chronic, inflammatory arthritis (psoriatic arthritis) that leads to joint deformations and disability. Between 4.2% and 69% of all patients suffering from psoriasis develop nail changes. Individuals with psoriasis are reported to be at increased risk of developing other serious clinical conditions such as cardiovascular and other non-communicable diseases (NCDs).

Psoriasis causes great physical, emotional and social burden. Quality of life is often significantly impaired. Disfiguration, disability and marked loss of productivity are common challenges for people with psoriasis. There is also a significant cost to mental well-being, such as higher rates of depression, leading to negative impact for individuals and society. Social exclusion, discrimination and stigma are psychologically devastating for individuals suffering from psoriasis and their families. It is not psoriasis causing the exclusion – it is largely society’s reaction to it and this can change.

Treatment of psoriasis is still based on controlling the symptoms. Topical and systemic therapies as well as phototherapy are available. In practice, a combination of these methods is often used. The need for treatment is usually life-long and is aimed at remission. So far, there is no therapy that would give hope for a complete cure of psoriasis. Additionally, care for patients with psoriasis requires not only treating skin lesions and joint involvement, but it is also very important to identify and manage common comorbidity that already exists or may develop, including cardiovascular and metabolic diseases as well as psychological conditions.

In 2015, the notion is that psoriasis is a complex disease leading to numerous consequences for patients’ lives.

Is psoriasis becoming more or less common?

Tracking trends in incidence and prevalence of psoriasis is difficult, due to the different methodologies of research on this issue. However, an apparent upward trend is observed in several countries. The prevalence of psoriasis in China in 1984 was 0.17%, while 25 years later, another study found it to be 0.59%.

The prevalence in Spain in 1998 was 1.43%, while 15 years later it was reported as 2.31%. Data on the prevalence in the United States from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey indicated an increase in prevalence from 1.62% to 3.10% from 2004 to 2010. However, different methodologies of conducting these studies, especially in view of the various case definitions of psoriasis, do not allow for a clear assessment of the increasing trend.

The most instructive study of trends in prevalence is a 30-year follow-up of a population-based cohort in Troms., Norway. Analyses of trends in prevalence during 1979–2008 indicate that self -reported lifetime prevalence of psoriasis (in the same cohort) has increased from 4.8% to 11.4%

How does psoriasis affect people's lives?

Psoriasis is a chronic, non-communicable, painful, disfiguring and disabling disease for which there is no cure, presenting without a single, typical clinical picture. It can manifest in many different forms. In addition to the involvement of skin and nails, inflammatory arthritis (psoriatic arthritis) may develop. Patients suffering from psoriasis are at higher risk of developing cardiovascular and other NCDs. Moreover, psoriasis affects mental health and people suffering from the disease experience significant social stigma.

In assessing the severity of psoriasis, more than 40 different tools are being used. Commonly used measures for scoring the severity of psoriasis include the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI), and the Physician Global Assessment. Clinicians assess the severity of the disease, taking into account the degree of scaling, redness, thickness of the skin lesions or the size of the BSA occupied by psoriasis. QoL measures are also important.

Psoriatic arthritis

In addition to the skin, psoriasis can be associated with an inflammatory arthritis known as psoriatic arthritis, which involves the joints of the spine and other joints. This occurs without presence of specific antibodies in the blood (seronegative spondyloarthropathy). The rheumatoid factor (antibody occurring in rheumatoid arthritis) is also negative.

A review of the literature showed that psoriatic arthritis affects between 1.3% and 34.7% of patients diagnosed with psoriasis. There are no data on sex predilection. In a United States population, it was observed that psoriatic arthritis occurred more frequently in Caucasian patients than in other ethnic groups. Two large consecutive German studies from dermatological practices that assessed the prevalence of arthritis from examinations by rheumatologists in 2005 and 2007 was 20.6% and 19.6%, respectively.

The clinical symptoms are variable, however, peripheral arthritis, spondylitis, enthesitis (inflammation of the sites where tendons insert into the bone), arthritis in the fingers and dactylitis (profuse swelling of the fingers or toes) are considered to be most common. Psoriatic arthritis can lead to chronic pain and change in physical appearance. Patients suffering from psoriatic arthritis have reduced physical fitness, compared to psoriasis patients without it. Typically, psoriatic arthritis occurs in conjunction with longstanding skin lesions, although rarely it occurs alone, in the absence of psoriasis.

Associated diseases

Numerous studies have reported the coexistence of psoriasis and other serious systemic diseases, most often mentioned are cardiovascular diseases, metabolic syndrome, including hypertension, dyslipidaemia and diabetes mellitus, and Crohn’s disease. Even children show increased rates of comorbidity compared to unaffected infants, or those with atopic eczema.

Most publications discuss the association between cardiovascular disease and psoriasis. Patients diagnosed with psoriasis have an increased burden of subclinical atherosclerosis and vascular inflammation. They also have significantly higher levels of serum lipids, including triglycerides and total cholesterol, compared to healthy individuals. Moreover, psoriasis is associated with atrial fibrillation and stroke, which may be aggravated in young patients. However, it should be noted that at present it is not known whether psoriasis is an independent risk factor for the development of cardiovascular disease. Obesity or weight gain has been shown to be an independent risk factor for psoriasis. Tobacco smoking is another risk factor. Frequency of metabolic syndrome, depression and erectile dysfunction has also been found to be significantly higher in patients diagnosed with psoriasis. In some diseases and subgroups of patients, psoriasis has been shown to be an independent risk factor for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. In spite of a high number of studies on the association of psoriasis with comorbidity, the causality and independence on some associated diseases remain unclear and need further research.

Psychological and mental health

Psoriasis is not only a disease that causes painful, debilitating, highly visible physical symptoms. It is also associated with a multitude of psychological impairments. For many reasons, psoriasis can be psychologically devastating. Patients’ lives become especially difficult when psoriasis is present in highly visible areas of the skin such as the face and hands. Related psychological problems can affect every day social activities and work. It causes embarrassment, lack of self-esteem, anxiety and increased prevalence of depression. Patients with psoriasis report experiencing anger or helplessness, and they disclose a higher rate of suicidal ideations than other patients. In a study of 127 patients with psoriasis, 9.7% reported a wish to be dead and 5.5% reported active suicidal ideation at the time of study.

Influences from the workplace

In the workplace, psoriasis may be triggered or aggravated by mechanical or other physical impact on unprotected body locations. In patients who claimed occupational hand dermatitis, psoriasis was found to be the cause of the disease in 3.8% –6.5% of cases. Special gloves and other personal protective equipment may reduce lesions and enable the person to continue working, which otherwise maybe jeopardized.

Principles of psoriasis management

Psoriasis is by nature a chronic, incurable disease with an unpredictable course of symptoms and triggers. The consequence is often life-long treatment; therefore, all treatments must meet high quality criteria that are not only efficacious, but also safe over long periods. As the cause of psoriasis is still unknown, treatment is only available to control symptoms. Treatments include a range of topical and systemic therapies as well as phototherapy. It also involves treatment for reducing pain and disability from arthritis and other manifestations.

Care for patients with psoriasis requires more than management of the skin lesions and joint involvement. The complexity of psoriasis means that prescribing drugs in isolation is insufficient to control the disease and a holistic, whole person approach to care is needed. Management of psoriasis also includes screening for associated diseases such as hypertension, dyslipidaemia, diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disorders as well as their complications such as myocardial infarction and stroke. Psoriasis patients are more likely to suffer from depression and anxiety disorders and have an increased rate of suicidal ideation. Screening at regular intervals for these associated diseases and for co-medication to prevent interactions between medications or medicine-triggered psoriasis as well as recognition of trigger factors and their treatment are an essential part of psoriasis management.

Management algorithms for countries with a developed social and health-care system can be adapted to the needs of local health-care environments. Psychosocial interventions may be needed such as psychological treatment, patient education and psychotherapy. One-to-one sessions, group therapy, nursing intervention and support by phone or telemedicine may also be helpful. Patient empowerment is a central component of successful programmes, as has been demonstrated in other chronic skin diseases.

Treating the skin manifestations

There are three major forms of therapy – topical therapy; phototherapy; and systemic therapy Treatment is based on psoriasis severity at the time of presentation. Mild psoriasis usually is treated with topical therapy, progressing to phototherapy in the case of insufficient response. Moderate to severe psoriasis requires systemic therapy. Commonly used is a range of first-line medicines. In some countries, other systemic therapies are available. All treatments for psoriasis, apart from retinoids, are primarily anti-inflammatory, and subsequently lead to slowed epidermal keratinocyte turnover and a flattening of plaques. In many countries, other treatments may play a prominent role, including traditional Chinese medicine, self-treatment with over-the-counter products (non-prescription medicines) and climatotherapy.

Understanding triggers

Several triggering factors have been identified leading to the first manifestation of psoriasis or flares of a stable chronic disease. Understanding and minimizing these triggers can be an important part of managing psoriasis. In a number of studies from different countries, obesity/weight gain has been identified as a significant trigger for psoriasis. Studies have shown that obese psoriasis patients undergoing bariatric surgery with subsequent significant weight loss show improvement of skin lesions. Obesity is also associated with reduced efficacy of psoriasis treatment and is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Thus, weight loss intervention programmes should be part of psoriasis management. Tobacco smoking is another important risk factor for psoriasis. Counselling for smoking cessation should be included in caregiving. Certain infections can also serve as triggers for psoriasis. Streptococcal throat infection is one important aggravating or initiating factor. Periodontitis has also been associated with an increased risk for psoriasis. Tonsillectomy in adult patients with recurrent tonsillitis can improve the course of psoriasis and reduce the need for therapy. Stress represents a strong aggravating factor for psoriasis in both adults and children, regardless of the nature of the stressor.

Lack of awareness of health professionals

An insufficient number of health professionals results in a lack of specialist support to general practitioners, who are the lone providers of health care. Lack of adequate training of general practitioners and other health-care providers, results in a low awareness of psoriasis. Ultimately, lack of awareness about psoriasis and its associated co-morbidities results in under-diagnosis and ineffective therapy, inappropriate to the needs of the patient

Paper on Psoriasis Care

In circumstances where there is limited access to health professionals, the lack of access to medical specialists, including dermatologists, rheumatologists, psychiatrists, cardiologists and paediatricians, is even more likely. In an ideal situation, contact with such specialists is needed to ensure the optimal treatment of psoriasis and prevention and management of attendant co-morbidities.